Stonehenge is one of the most famous prehistoric sites in the world, yet it remains shrouded in mystery. There is still so much that we don’t know and may never know about its origins or function, and this mysteriousness only makes it more intriguing.

However, this isn’t to say we don’t know anything about the site. On the contrary, years of research and study have brought new insights into its long history, some of which have only added further questions. And, as we’ll see, though abandoned, history has a habit of playing out in and around these ancient stones.

With that in mind, here are ten things you might not know about Stonehenge.

Related: 10 Most Plausible Pyramid Construction Theories

10 Its Construction Was Completed in Stages

We don’t exactly know how or why Stonehenge came to be, but we do know it wasn’t the handiwork of one group of people. Instead, Stonehenge’s construction is something that occurred over hundreds of years. Furthermore, it was altered multiple times by several generations.

Initial construction on the Stonehenge site began around 5,000 years ago with the digging of a ditch and bank using primitive tools. However, the Stone circle was built several hundred years later, around 2500 BC. Work continued until around 1600 BC, with the bluestones, in particular, seeing a lot of movement.[1]

9 Some Stones Were Sourced from Hundreds of Miles Away

Some of the bluestones that make up the inner ring of Stonehenge can be traced to Preseli, Wales, which is nearly 300 kilometers (180 miles) away. Just how these stones made it across land and water to Stonehenge still confounds archaeologists and scientists alike. Some have suggested glaciers gave a hand. Others maintain that humans did all the work.

In 2000, a Welsh group was determined to discover how ancient peoples could have accomplished this feat. To do this, they set about trying to recreate the journey of a large bluestone using only stone-age tools. Unlike our ancestors, though, they were unsuccessful. They abandoned the project shortly after the stone ended up in the water.[2]

8 Charles Darwin Studied Worms There

When people think of Charles Darwin’s research travels, the first thing that comes to mind are the Galapagos islands and his study of the finches. However, the world’s most famous biologist, Darwin, best known for his theory of evolution, once traveled to Stonehenge to conduct research.

You might not think Darwin’s work would see him take much interest in stones, and you’d partly be right. See, it was not the stones he was interested in but the worms (a favorite subject of Darwin’s) that lived beneath them. Darwin was particularly fascinated by how the tiny worms there had caused an enormous fallen stone to sink deeper. Some of his findings from his research there ended up in his final book: The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms.[3]

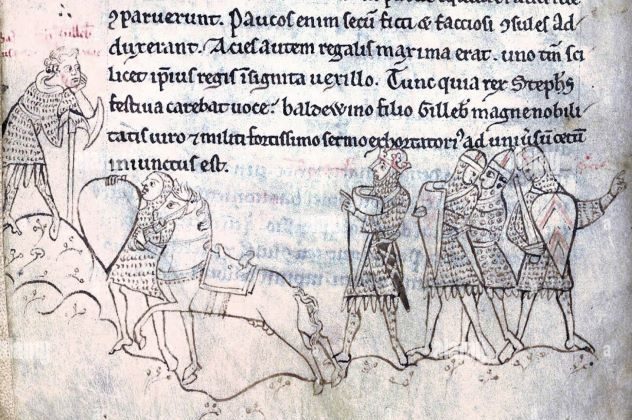

7 First-Known Direct Reference Dates to 12th Century

It makes sense that the ancient civilization that built Stonehenge didn’t leave us any written records. But, what’s fascinating, is that in the hundreds and thousands of years that followed, no one else did either. At least they didn’t leave any records that have survived anyway.

Stonehenge’s first-known written reference is dated to the 12th century and was written by a man named Henry of Huntingdon. He was the archdeacon of Lincoln at the time and was compiling a history of England. In the book that followed— Historia Anglorum or History of the English—he would describe the stone circle as a “manner of doorways.” Meanwhile, it wouldn’t be until the 15th century that the first-known accurate drawings of Stonehenge began to appear.[4]

6 Stonehenge’s Function Is Still Unknown

Archaeological evidence suggests that Stonehenge served as a burial site, but what other functions it provided remain a mystery. Some scholars have theorized that the monument served a religious function, either as a ceremonial site, pilgrimage destination, or memorial to the deceased.

One theory that gained a particular amount of attention is the idea that it served as a kind of astronomical calendar, one which corresponded to the yearly equinoxes and solstices. Evidence does, in fact, show that the stones align with the sun during important turning points of the year, including Midsummer and the winter solstice. However, it is debatable whether the stones ever aligned with the moon, stars, and planets.[5]

5 Is It a Henge or Non-Henge?

The truth is that Stonehenge is neither the largest nor the oldest henge—in fact, it’s not even a proper henge at all.

Stonehenge has become an iconic part of the British landscape and attracts around 800,000 people a year. But while it may be the most famous, it is neither the largest nor the oldest. For example, the Avebury henge, which is only 17 miles away, is both larger and older. Ironically, Stonehenge is not technically even an actual henge as it doesn’t meet the criteria, even though the term henge is derived from its name. While Stonehenge has an earthwork circle surrounding it, the location of the main ditch outside the main bank demotes it to an “almost-henge.”[6]

4 Duke Digging for Treasure

Interest in Stonehenge isn’t exactly a recent phenomenon, and the site has been subject to several digs and excavations over the years. Most of the time, these digs were conducted in the pursuit of knowledge. But in the early 17th century, one man had something else in mind: treasure.

In 1620 the Duke of Buckingham sent his men to dig in the monument’s center in search of lost riches. Unbeknownst to them, however, they were digging into a prehistoric pit. They found plenty of bones and skulls of animals and burned charcoal, but neither the men nor the duke left the place any richer.[7]

3 It Was the Subject of a Battle

In 1985, Stonehenge would be at the heart of a violent clash between a group of travelers and police, one that would become known as the “Battle of the Beanfield.”. Unsurprisingly, accounts of the battle vary depending on whom you ask. Some remember it as a successful operation conducted with the support of the local community. But for others, it was nothing more than a violent ambush.

The travelers, a group of some 600 people, wanted to stage a free festival at the monument. Fearing the drug use and lawlessness that had occurred at previous events, the police sought and obtained an injunction to prevent the festival. However, the traveling convoy was unswayed and tried to go ahead with their plans. It all culminated in violence between the two groups. Eight Officers and sixteen travelers would be injured in the brawl that ensued, and multiple vehicles were damaged.

Courts would later clear the police of unlawful arrest but awarded compensation to the convoy for damage caused.[8]

2 Numerous Legends and Myths Regarding Its Origin

Whenever there are unanswered questions, there will inevitably be some myths and legends to fill the space. And such is certainly the case when it comes to Stonehenge. One of the oldest and most well-known of such myths is the folk tale that suggests the Artheriun Wizard Merlin is responsible for creating the monument. The story goes that Merlin teleported the stones from Ireland, where Giants had assembled them.

Another legend points to invading Danes as the source of its origin; others describe the monument as a Roman temple. Modern tales are no less imaginative with the suggestion that the site is, in fact, a UFO landing pad, perhaps being the most famous.[9]

1 The Site Was Used as an Airfield

Stonehenge sits upon a relatively flat and open expanse of land, which made it a surprisingly popular site for aviation use in the past. And while you wouldn’t think to look at it now, the area once hosted military aircraft and hangers.

Planes first arrived on the site in 1909 and were civilian in nature. However, during the First World War, the British government, desperate for new airfields, took an interest in using the site. As a result, the area around Stonehenge would be requisitioned and swiftly turned into an aerodrome in 1917.

The site served as a final training ground for pilots before heading to the Western Front. Its existence would be brief, though, and in 1919 the site was handed back to the original owner. Eventually, the buildings were removed as part of an initiative to return the monument to its natural surroundings. Today, it seems almost as if the site of the airfield never existed.[10]