The narrator of Edgar Allan Poe’s 1835 short story “Berenice” asks a disturbing question: “How is it that from beauty I have derived a type of unloveliness?” What if the narrator had asked this question in reverse, as “How is it that from unloveliness I have derived a type of beauty?” How much more disturbing might have been the inquiry?

This list of 10 eerie works of art inspired by horrific events offers an answer to our question, and the answer is disturbing, indeed

Related: 10 Crazy Things That Make Us Love Or Hate Art

10 Ten Breaths: Tumbling Woman II by Eric Fischl

The “Tumbling Woman” part of the title of Eric Fischl’s bronze sculpture, Ten Breaths: Tumbling Woman II (2007-2008), seems self-explanatory. However, it poses several significant questions. Why is the tumbling woman naked? If she is a gymnast, why isn’t she clothed? Why are her earthen skin tones streaked with red-orange? Why is she tumbling? What accounts for her awkward landing on her head, neck, and upper left shoulder? Such questions indicate that there is more to Fischl’s portrait of the tumbling woman than meets the eye.

The mystery is solved once the context, the painting’s origin, is revealed. The text on the plaque that accompanies the statue reads: “We watched, disbelieving and helpless, on that savage day. People we love began falling, helpless and in disbelief.” “That savage day” was September 11, 2001, when al-Qaeda perpetrated a series of attacks against the United States.

In one of these attacks, the terrorists piloted two hijacked airplanes into the World Trade Center in New York City. As a result, some people leaped from the towers’ upper floors to avoid burning to death inside the buildings. As the Smithsonian American Art Museum points out, the sculpture’s depiction of “the vulnerability of the human body…takes on special significance in this tragic context.”[1]

9 The Raft of the Medusa by Theodore Gericault

The pyramid of desperate human figures in Theodore Gericault’s oil painting The Raft of Medusa (1818-1819) calls attention to the pathos of their plight, as does the steep pitch of the approaching wave, the force of which can almost be felt. Some of the figures are clothed. Others are half-dressed. Still, others are naked. Their lack of attire suggests that their departure was headlong and sudden, underscoring the panic they felt as they’d piled onto the raft, a precarious perch amid tempestuous seas. Closer attention to the passengers suggests that one or two among them are dead or dying. In a corner of the planks, a body lies, supine and listless, its head back. Another lies half-on, half-off the raft, head underwater.

As Dr. Claire Black McCoy observes, the subject of the painting, which was exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1819 and is now displayed in the Louvre, would have been recognized by those who saw it in the Salon. The July 1816 event it depicts, which had recently appeared in the news, would become “a political scandal.” Officials aboard the French naval ship Medusa, including the governor of Senegal and his family, McCoy explains, were headed for the colony to secure its French possession and assure the continuation of the covert slave trade, even though France had officially abolished the practice. En route, the captain accidentally ran the ship aground on a sandbar off the coast of West Africa.

When the ship’s carpenter was unable to repair the damage, the governor, his family, and other high-ranking passengers boarded the six lifeboats. The remaining passengers—nearly 150—were left behind to fend for themselves aboard a raft the carpenter constructed from the ship’s masts. Of their number, fifteen were rescued, of whom only ten “survived to tell the tale of cannibalism, murder, and other horrors aboard the raft.”[2]

8 Grey Day by George Grosz

At first glance, George Grosz’s art often suggests ordinary incidents of everyday life. However, the grotesquery of his portraits, a common feature of his work, hints that the occasions he depicts may involve more than is initially apparent. His post-World War I painting Grey Day (1921) is no exception. A worker carrying a shovel strides briskly past a factory and its smoking chimney, while a businessman walks toward the viewer, down a narrow sidewalk alongside a building.

Before them, but behind another figure, a grim, angular, scar-faced, one-armed veteran in uniform walks along, carrying a cane. There is a partially-constructed brick wall between him and the figure before him, a wealthy, cross-eyed man who struts past in the opposite direction. He wears an expensive suit and carries a briefcase and an L-shaped ruler. His tool suggests that he may be a carpenter engineer. Outwardly, he is a man of respectability. However, his crossed eyes and the scars on his egg-shaped head, implying, perhaps, that he is an “egghead,” suggest that he, too, has experienced violence personally.

According to an article by the Tate, the British art institution, Grosz’s painting “illustrates how the wealthy profited from war [while] the disabled and forgotten veteran was left poor and divided from society.” This is revealed by the partially-built wall indicating the separation of “the two groups.” The wall itself, the Tate article suggests, is ambiguous to the extent that “the viewer [must] decide whether this half-built wall is being constructed or brought down.”[3]

7 Big Electric Chair by Andy Warhol

After their conviction for espionage against the United States, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were electrocuted on June 19, 1953. Although Julius succumbed quickly, dying after the receipt of one shock, his wife survived three applications of electricity. The fourth charge finally killed her but caused a “ghastly plume of smoke [to rise] from her head.” Irene Philipson notes, in Ethel Rosenberg: Beyond the Myths. Ethel experienced a much harder death than her husband had.

Andy Warhol pioneered silkscreen painting, which allows “the artist to translate photographs as multiple, ‘mass produced’ works.” Initially, he used this mechanical printmaking process to market pictures of celebrities and everyday objects. However, his work later depicted more macabre subjects in his Death and Disasters series.

One of these paintings, Big Electric Chair (1967-1968), was inspired by a press photograph of the execution device taken inside Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York, where the Rosenbergs were put to death. Perhaps Warhol’s gruesome series was intended to desensitize viewers to the horrors of existence his paintings depicted. “When you see a gruesome picture over and over again,” he maintained, “it doesn’t really have an effect.”[4]

6 Guernica by Pablo Picasso

A bull, a horse, bodies and body parts, terrified faces, a broken sword clutched in a dying man’s fist, a woman in agony—these are some of the macabre images in Pablo Picasso’s nightmarish Guernica (1937). According to a website devoted to the artist, the commissioned work represents Picasso’s immediate reaction to the Nazis’ devastating casual bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

The mural, painted in black, blue, and white oils, is an amalgamation of pastoral and epic style showcasing “the tragedies of war and the suffering it inflicts upon individuals, particularly innocent civilians.” The lack of colors expresses the “starkness of the aftermath of the bombing.” Although interpretations of the painting differ, the rampaging bull is thought to symbolize fascism, while the horse represents the people of Guernica, a stronghold of the Republican forces who resisted the Nationalists led by Francisco Franco.[5]

5 The Course of Empire: Destruction by Thomas Cole

For hundreds of years, starting in 27 BC, the Roman Empire essentially was the Western world. Although the Empire was by no means an earthly paradise, it did provide law and order, protection, and a way of life for a vast region of the Middle East and Europe. During the Pax Romana, or “Peace of Rome,” which lasted about 200 years, art and culture flourished in the Empire. To Roman citizens, it probably appeared that the Empire would exist forever. However, when Rome finally fell to barbarian invaders, it must have seemed to them that life itself had come to an end. Indeed, life as they had known it had changed drastically.

Not surprisingly, this catastrophic event became the subject of several paintings, one of which, Thomas Cole’s The Course of Empire: Destruction (1836), dramatically envisions this monumental event. Displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the painting pictures great armies contending for victory during a dark storm against the backdrop of the city in flames. A flotilla of enemy ships (of unlikely Viking origin) besieges the defenders. One of their vessels is used to cross a gap between sections of a bridge leading to the steps and rooftops of buildings where Roman centurions have made a desperate stand.

Although a ship sinks, it is clear that the invaders have gained the upper hand. Many Roman soldiers are dead or lie dying. The city has been put to the torch. At the edge of a rooftop, one of the barbarians arrests a terrified Roman lady intent upon casting herself into the sea. A larger-than-life statue of a Roman soldier, rushing forward with shield aloft, symbolizes the fall of the legion and the imminent fall of Rome itself: part of the sculpture’s head lies broken on the rooftop below. The panoramic painting is a sweeping vista of the disaster that has befallen the Empire and its citizens.[6]

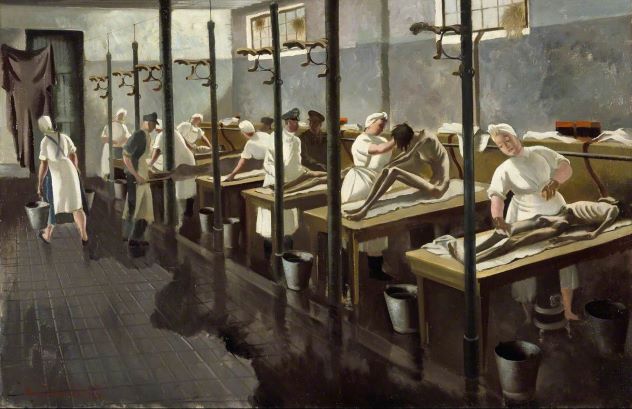

4 Human Laundry by Doris Clare Zinkeisen

The Nazis’ dehumanization of Jews is indicated by the title of Clare Zinkeisen’s stark 1945 painting Human Laundry: Belsen, 1945, which is displayed in the Imperial War Museum in London. Painted mostly in grays and whites, the work shows a row of skeletal figures laid out, on their backs, atop rough tables. German nurses, supervised by a uniformed German military doctor, bathe them with soap and the water kept in pails at the ends of the tables. A pair of bearers has just arrived with the covered body of another item of “human laundry.” Or, perhaps, they are removing a body that has ceased to survive the harsh extremes of the Belsen concentration camp.

As a set of notes concerning the painting states, “Zinkeisen finds an effective motif in the contrast between the well-fed, rounded bodies of the German medical staff and the emaciated bodies of their patients.” This effect is heightened by the unconcerned looks on the nurses’ faces as they go about their duties; by the resigned and hopeless postures of the prisoners they handle, whose faces are not shown, further heightening their dehumanization; and by the nurse who nonchalantly carries a pair of buckets past the tables beside a long puddle of spilled water that has collected on the floor. The medics are nurses and doctors from a nearby German military hospital pressed into service to wash and de-louse the prisoners to prevent the spread of typhus before they could be admitted to the makeshift Red Cross hospital nearby.

Another set of notes offers additional information concerning the plight of the World War II prisoners and the theme of the painting: “The ‘human laundry’ consisted of about twenty beds in a stable where German nurses and captured soldiers cut the hair of the inmates, bathed them, and applied anti-louse powder before their transfer to an improvised hospital run by the Red Cross.”(LINK 9) [7]

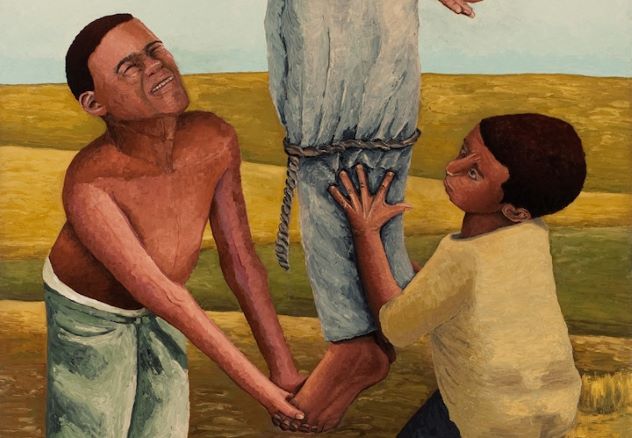

3 Stories Behind the Postcards by Jennifer Scott

Jennifer Scott’s 2009 series of paintings and collages, Stories Behind the Postcards, was exhibited in America’s Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The inspiration for them, she said, were souvenir postcards which, according to the museum’s website, “depicted images of lynching [and were] mailed around the country.” Such lynchings occurred between the 1880s and the Second World War. Upon seeing the cards, Scott wondered about what she did not see in them, such as “the family members left behind to take down the victim, to mourn and bury the remains—if there was enough to bury.”

Her objective in creating the series, she said, was to encourage viewers to relate to the plight of the victims and to “try to imagine the victim’s life before death was captured in a postcard.” In addition, she hoped to move the viewer “beyond typical politically correct thoughts and feelings about race and race relations” so that their reflection on her work and its subject matter might have a lasting impact on the next generation.

Concerning three of her paintings, Three Generations, The Impossible (pictured), and My Son, My Grandson, Scott explained that unlike the postcards—which were in black and white or sepia-toned, her paintings are in full color. Without the color, the viewer might be able to distance themselves from the disturbing images. However, her versions remind the world that “these horrors took place amidst the beauty of nature and often in clear daylight.” Three Generations shows a middle-aged woman comforting an anguished older woman who is “beside herself with anger and sadness” as she leans over the victim, a young woman who, Scott explained, was lynched after being raped.[8]

2 The Price by Tom Lea

The Price (1944) is a gruesome reminder of the cost that individual fighters paid on the World War II battlefield. A U.S. Marine advancing across a field in Peleliu in 1944, amid thick smoke on the ground and in the air, seems to stagger. The left side of his face, his left shoulder, the left side of his chest, and his left arm are shredded and bright red with his blood. That Marine, the artist, Tom Lea, explained, was “hit with a mortar blast, staggered a few yards like that, and just fell down.” The Price hung outside of Eisenhower’s office at the Pentagon after the war, the artist added, “to remind him of the price of war.”

Adair Margo, a gallery owner and friend of the El Paso, Texas, artist, said, “He was the only eyewitness painter of the war who depicted shots being fired and U. S. soldiers being blown apart with blood and guts on the ground.” Lea’s artwork, Margo added, represents honest portrayals of the truth of war, then and today. Two reasons that Life dispatched Lea to paint the war, Margo said, were that Lea “could paint battle in color, when photography was in black and white,” and he had the skill to “piece together parts [of the fighting] to communicate the whole of battle.”

Larry Decuers, the curator of The National World War II Museum in El Paso, said that the Life and World War II exhibit of Lea’s paintings from the U.S. Army’s art collection, on loan from the U.S. Army Center of Military History, included twenty-six images which Lea painted during the war. The paintings in the exhibit were the ones that appeared in Life magazine during the conflict itself, offering readers a no-punches-pulled glimpse of the war. During the U.S. operation against an entrenched Japanese force at Peleliu, 1,100 Marines died and 5,000 were wounded, while virtually all 11,000 Japanese soldiers on the island were killed.”[9]

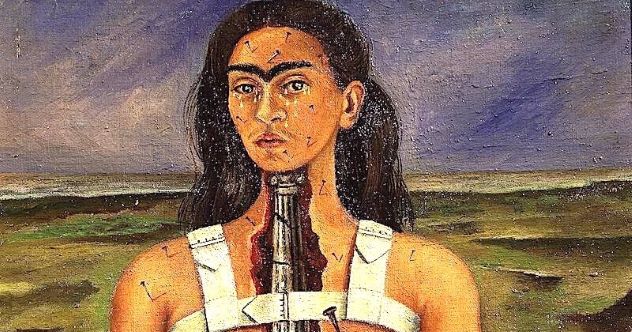

1 The Broken Column by Frida Kahlo

Not all catastrophes are criminal, martial, social, or political, and they don’t all affect entire groups or nations. The tragedy that befell Mexican artist Frida Kahlo was accidental and personal. It was also responsible for the vast majority of her work as an artist. Her paintings largely depict her physical disabilities and suffering and their effects on her personal life.

Kahlo, who suffered from polio as a child, nearly died in a bus accident as a teenager. She suffered multiple fractures of her spine, collarbone, and ribs, a shattered pelvis, a broken foot, and a dislocated shoulder. Soon after this devastating accident, Kahlo adopted painting as a way to cope with and overcome her ordeal, the effects of which continued throughout her life. “From the outset of her recovery,” a website dedicated to the artist explains, “she began to focus heavily on painting while in a body cast.” Despite having 30 operations, she persisted in painting largely autobiographical, if symbolic, portraits of herself.

The Broken Column, a 1944 portrait of the artist, shows Kahlo topless, her arms at her sides, weeping as she gazes toward the viewer. A sheet is wrapped around her hips, and an orthopedic corset composed of straps over her shoulders and around her torso binds her abdomen. She is split by a large, wide fissure that shows, in place of her spine, the somewhat broken column of the painting’s title. The fissure, or cleft, writes art historian Andrea Kettenmann, author of Kahlo, becomes a symbol “of the artist’s pain and loneliness.” Another symbol of Kahlo’s pain is the nails that pierce her face and body. What Kettenmann states about another of Kahlo’s painting The Landscape (1946-1947) is also true of The Broken Column: “The desolate and fissured landscape [suggestive of the artist’s broken body] provides the background for Frida Kahlo’s work.”[10]