Anyone with even a passing interest in etymology will be well aware that many English words come from Latin, the language of ancient Rome. While English is officially considered a Germanic, rather than a Romance language (the latter being languages rooted in Vulgar Latin rather than those best suited to whispering endearments to your sweetheart,) it borrows liberally from many different sources.

Perhaps borrows is too mild a term though; more accurately, English follows other languages down dark alleys, knocks them over the head and goes through their pockets for loose vocabulary. As such, this mongrel tongue of ours contains no small amount of Latin-based terms.

The following 10 words have been selected because of their interesting origin stories, surprising initial usage or the way the meanings have been altered slightly over time. Or, in some cases, all three. While by no means exhaustive, these are some of the more noteworthy terms from ancient Rome still used today.

10 Truly Disgusting Facts About Ancient Roman Life

10 Decimate

The term “decimate” as used today refers usually to a significant defeat or the loss of a large but unspecified number, as in “the plague decimated the population of Europe.” The term, first used in an ancient Roman military context, rightly applies to eradication and destruction but is, in fact, very specific as to the numbers involved.

We all know that the prefix dec refers to the number 10, hence terms like decade and decimal. As such, decimation refers to reduction by a tenth, which is exactly how it was used as a punishment in the Roman legions. Military units that mutinied or were otherwise thought to have underperformed in battle were decimated— one in every ten soldiers were selected at random and put to death in the most gruesome manner possible: by being beaten to death with sticks by their comrades.

Not the best way to go, to be sure, but this method of punishment, by being entirely random, encouraged soldiers to not only give their best by way of loyalty and performance but also to encourage their fellow troops to do the same. It proved largely successful, given the formidable reputation of Roman military might at the time. It was also probably considered to be a fair measure by the soldiers themselves. At least by 9 out of every 10 legionnaires, anyway.

9 Circus

One generally associates this word with either performing animals and acrobatic acts or large family gatherings and while the modern circus as we know and love it today came into being in England, during the 18th century, the term itself is of far older origin, dating back to ancient Rome.

Now, circumventing a lengthy explanation of the derivation of the word, suffice it to say that it has the same root as “circle”, and, accordingly, simply refers to something round. Ancient Roman amphitheaters were thus called circuses, due to their shape, and circus arenas today are similarly spherical, with the leader commonly referred to as the ringmaster. There the similarities end, however, as the Roman variety was used to stage blood sports, such as chariot racing and gladiator fights. Not exactly the ideal place for a family outing, then.

Some modern circus traditions are a holdover from those times though, such as employing the use of trained animals. Some people condemn the circus industry for the treatment of their non-human performers, and rightly so – in ancient Rome at least the lions got to eat a man or two for their troubles. The most famous Roman amphitheater was the Circus Maximus, which operated for over 1000 years. Given that it roughly translates to “big round place”, one has to imagine that the guy who came up with the name was not being paid for his creativity.

8 Urine

The English word “urine” which, of course, refers to the liquid waste product produced by the kidneys, comes from the Latin “urina”. While the substance is largely considered useless today, that wasn’t always the case. The Romans not only popularized the term but put the stuff to wide use, so much so that Emperor Nero imposed a “urine tax” on his citizens in the 1st century AD.

Some of these uses were surprisingly inventive. Of course, human waste products were commonly used in leather tanning throughout history, but the Romans took things a step further, using urine as both a cleaning agent and a beauty product. Due to its unique chemical composition, urine made for excellent early laundry detergent and, because it was believed to make teeth appear whiter, was also commonly used as a mouthwash and in toothpaste. They might have been on to something there, as urine was widely used in dental hygiene products up until as recently as the 18th century.

Ever the inventive pioneers, the Romans also used urine as invisible ink to write secret missives between the text of official documents. Such messages were visible only when heated, making them a brilliant early espionage tool, although it’s hard to imagine a modern James Bond resorting to such measures. In any event, that’s where the saying “read between the lines” comes from. One could say, then, that all of this proves the expression “piss poor” is largely inaccurate, historically speaking.

7 Triumph

On the other end of the spectrum from decimate, we have triumph, a term generally used in both verb and noun form to refer to a victory or success. In ancient Rome, a triumph was the name given to the victory parade and celebrations awarded to a victorious General upon his return to the city.

A triumph was awarded by the senate, and a victory had to meet certain criteria to qualify; namely, a minimum of 5000 enemy casualties inflicted in a battle decisive in ending a war. Triumphs were such lavish affairs in honor of a single individual, that a slave was required to remind the victorious general of his mortality throughout the festivities, lest he mistake himself for a god. Victories that fell short of the requirements for a triumph could be awarded the lesser honor of an ovation, another term still very much in use today.

Only the best commanders ever received multiple triumphs; Pompey was awarded 3 in his lifetime, but, not to be outdone by his old rival, Julius Caesar in 46 BC granted himself 4 consecutive triumphs. Incidentally, the last of these was for his victory over the Pompey-led opposing faction in the civil war. Caesar’s triumph, however, was short-lived, as he was assassinated only 18 months later for fear he was becoming too powerful, probably causing that mortality-reminding slave the irrepressible urge to say: “told you so.”

6 Rubicon

![]()

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the word “Rubicon” as being a boundary line, the crossing of which commits one irrevocably. Nowadays, it is not uncommon to refer to an important occurrence from which there can be no going back as a “Rubicon” moment. The term was famously used by South African leader P.W Both in his 1985 Rubicon speech, although he illustrated the point not by crossing the figurative Rubicon but by shying away from it.

The original Rubicon moment occurred in 49 BC when Julius Caesar led the 13th legion across the small river Rubicon in Northern Italy in an act which committed him to a civil war. As provincial governor of the Cisalpine Gaul region, Caesar was forbidden from bringing his troops into the republic. When summoned to Rome to face charges of overreaching his command by his political opponents, Caesar crossed the Rubicon, the official border-line of Northern Italy, under arms thereby igniting the 3-year civil war that followed.

This momentous event also gave us the famous idiomatic expression “The die has been cast”, similarly referring to passing a point of no return. It is widely claimed that Caesar himself uttered this phrase upon crossing the Rubicon, but since this cannot be verified with any degree of accuracy, it may just be something that history had attributed to him for dramatic effect. We will probably never know for sure.

5 Kaiser

Continuing with the Caesar theme, the man is credited with many things still used today, such as the c-section birth method, the Julian calendar and even the 7th month of the year, named, of course, in his honor. He also “discovered” Britain, although the indigenous inhabitants he encountered already living there might have disputed the point. No matter, the British Empire would go on to “discover” many new lands of their own, similarly upsetting local populations, so it all evens out. One could even say Britain learned from the best – the original Mr. “I came, I saw, I conquered” himself.

Julius, of course, was the first Roman leader named Caesar, but not the last. His descendants would go on to further the family legacy, so much so that the early Germanic people simply referred to all Roman Emperors as Caesar. The word itself came to be synonymous with “emperor” and, over time, the leading Monarchs in Germany and Austria became known by the altered form of the word: Kaiser.

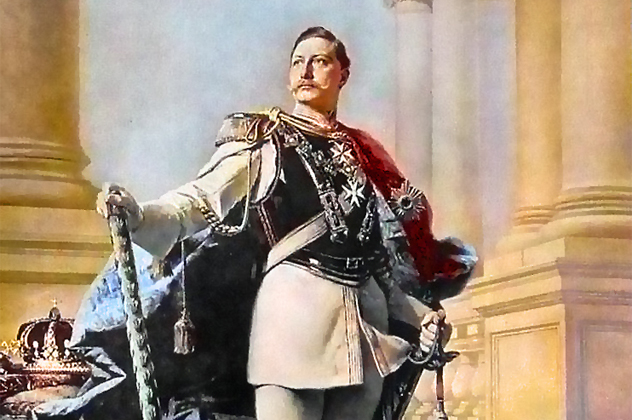

The last official Kaiser was Wilhelm II, the king of Prussia, who famously led Germany in WWI and was forced to abdicate his throne in 1918 towards the conclusion of the conflict. The term, like it’s Russian counterpart “Czar”, may have fallen largely out of contemporary use were it not for the famous South African based soccer team Kaiser Chiefs and the UK band of the same name which they inspired.

And for all that Caesar gave us, what did we do in return? Why, we named a certain chicken salad after him, of course. Go figure.

4 Plebian

We generally know this term as a common insult, particularly in its shortened form: “pleb”. It refers to something common, basic, possibly widely popular but lacking in sophistication. So a good description of reality TV, in other words. In 2012 British Conservative MP Andrew Mitchell was forced to resign amid the “Plebgate” scandal he ignited when he used the term to insult a group of policemen in a particularly colorful way, which I shall refrain from repeating here.

Of course, the term comes from ancient Rome, where it was not used as an insult but rather as a term of reference for the common masses; Roman citizens who were not of the patrician, senatorial or equestrian classes. It was the class-conscious British who turned it into an insult in the 17th century, when it became a euphemism for the lower class, or if you prefer, the unwashed masses. The negative connotations of the term persist to this day, as Mr. Mitchell discovered to his detriment.

The plebeians of ancient Rome may have been commoners individually, but collectively they made up a powerful group of working-class people that formed the backbone of the economy and represented a significant threat to the ruling class. Recognizing as much, the emperor Augustus aimed to keep them satisfied and distracted by way of food and entertainment respectively, thus coining the phrase “bread and circuses”. This method of appeasing the masses is, arguably, still employed today, and why not? It works, after all.

3 Salary

This has to be one of every employee’s favorite words, right up there with Friday, weekend and raise. The receiving of one’s monthly remuneration by way of a paycheck is not only necessary for survival but also usually serves as an indication of one’s worth in the workplace. The better you are at your job, the more you get paid. At least in theory, if not always in practice. The word “salary”, however, originally referred to a common condiment we generally take for granted nowadays.

Yes, the term salary comes from the ancient Roman custom of paying soldiers, not in gold, but in salt, something that was both practical and desirable, given its relative scarcity and considerable worth. The value of salt extended beyond ancient Rome, though; many civilizations used the sought after substance for trade and remuneration. That is the reason why a competent individual is still described as being worth his salt.

Much has since changed, and salt has become so ordinary and commonplace that food establishments practically give it away for free – a development that would have likely shocked a Roman soldier 2000 years ago. Sodium is generally something medical experts advise limiting in a healthy diet, and, I for one would be thoroughly unimpressed if my boss decided to pay me with a bag of salt at the end of the month. Still, the term remains, if not the custom itself.

2 Fascist

While one could argue that it was Benito Mussolini who put the “dick in dictator” the term itself, which means ruler with absolute power, came from his illustrious forebears in ancient Rome, as did the term fascism, that political system of which dictators are so fond. It’s only natural that the two words originated in the same place and time, for fascism refers to a “forcibly monolithic, regimented nation” under a dictator, so they go together like, well, bread and circuses.

In Roman times, the fasces was a bundle of rods tied around an ax and was carried by the magisterial attendants known as Lictors as a symbol of law and order. When carried inside Rome, the ax was removed to represent the right of the people to appeal a magistrate’s rulings. An exception was made in the case of dictators as well as generals celebrating a triumph. This symbol became synonymous with absolute authority and is believed to be where the term fascism comes from.

So Mussolini wasn’t exactly reinventing the wheel with his brutal leadership style, but he knew that – in a nod to his ancestral roots, his fascist party, established in 1919, bore as its symbol the traditional Roman fasces after which it was named. After all that it may be a bit anti-climatic to learn that the term simply means “bundle” in English, which sounds far less menacing than fascist and its brutal origins in Mussolini’s extreme left-wing principles.

1 Testify

Given that the Romans largely developed our system of law and order, it’s unsurprising that modern legalese abounds with Latin terms. Testify, the act of bearing witness or speaking under oath is no exception, but its original usage is more interesting than most. The contemporary custom when swearing an oath is to do so on a religious text, usually the Bible. Of course, that wasn’t an option in ancient Rome and, while they had a whole pantheon of gods to select from, they chose to instead swear on something perhaps a little closer to home.

One common theory is that the word derives from the Roman custom of swearing an oath on one’s testicles. Now, this is not 100% verifiable, and many opinions to the contrary exist. One such argument cites the fact that the word comes from the Latin “testis” which means witness. The counter-argument here is that the part of the male anatomy in question was so named because it bore witness to one’s virility. Indeed, the custom of swearing on the testicles, as nuts as it sounds, can be found in the Old Testament.

It’s unlikely we will ever know for certain, one way or the other. But the issue raises some interesting questions, like: shouldn’t we still be doing that? I mean, being tried for perjury for lying under oath is nothing compared to risking the old family jewels. We don’t know what happened to Romans who fabricated testimony, probably because no man in his right mind would have risked doing such a thing after taking the sacred oath. See? It’s nothing if not effective. Getting back to reality; clearly, the idea would never work today. Apart from being barbaric, in excluding women it’s also blatantly sexist, and we can’t have that. Still, it’s fun to imagine.